BHP case tests accountability

BHP is being sued for $70 billion over claims it destroyed a god.

BHP is being sued for $70 billion over claims it destroyed a god.

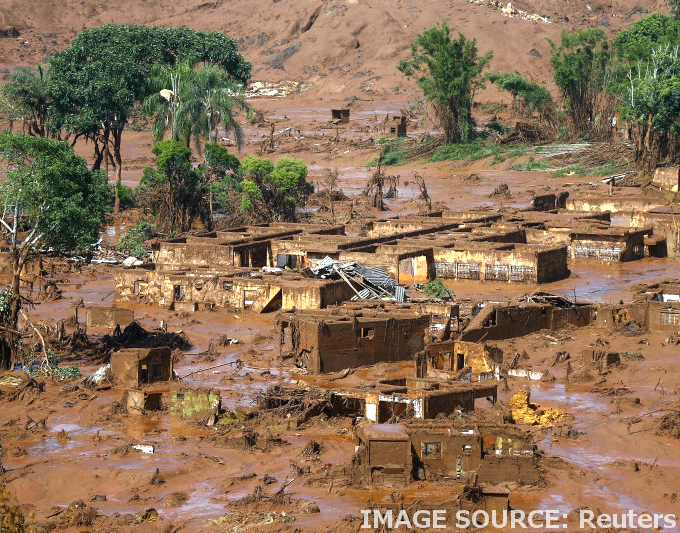

In 2015, the Mariana Dam in Brazil, co-owned by Anglo-Australian mining company BHP and local partner Vale, collapsed in one of the country’s worst environmental disasters.

Nineteen people died, and 600 kilometres of land and waterways were contaminated by toxic iron ore tailings.

The event is now the subject of legal action, as survivors, including Indigenous and traditional groups, seek justice in a London court.

Indigenous Brazilians, including the Krenak people, view the River Doce not merely as a source of sustenance but as a spiritual entity.

“When we say [the River Doce is our] father, we also mean like god, like a superior entity, the creator of everything,” Maycon Krenak, a chief of the Krenak people, said in a recent interview.

For them, the dam's collapse represented more than physical devastation - it destroyed a sacred entity integral to their culture and identity.

Krenak is one of the 650,000 claimants in a class action lawsuit against BHP in the United Kingdom.

Along with the Quilombolas, descendants of enslaved Africans, these groups argue that the environmental and cultural damage caused by the dam’s failure has yet to be properly compensated.

“We just want justice,” Krenak told Australian media during a visit aimed at lobbying Australian MPs and environmental groups.

He and others believe that the US$7.7 billion already spent by BHP and its partners on compensation and recovery efforts falls short.

They are now demanding AU$70 billion in compensation for the loss of their lands, livelihoods, and the destruction of their god.

Since the disaster, BHP has worked through the Renova Foundation to provide financial aid, build homes, and mitigate environmental damage.

The company insists that the water quality has improved, but local Indigenous and traditional communities dispute this, reporting that fish are diseased and agriculture remains impossible.

“We don’t feel safe eating the fish or anything that is around the river,” said Thatiele Monic, a Quilombola leader, who described the ongoing hardships her community faces.

For many survivors, the lawsuit is about more than financial reparations. It is about holding BHP accountable for the lasting impacts of the disaster.

“We want for them to acknowledge that they cannot come into our land and kill our people or kill our things without any consequence,” Monic said.

BHP, however, continues to defend its actions, stating that its legal obligations in Brazil are sufficient.

It also noted it had spent billions “on emergency financial assistance, compensation and repair and rebuilding of environment and infrastructure to approximately 430,000 individuals, local businesses and Indigenous communities”.

The company says the UK litigation is unnecessary, arguing that successful claimants in this case would not receive payments until 2028, which could undermine local recovery efforts.

“BHP Brasil is working collectively with the Brazilian authorities and others to seek solutions to finalise a fair and comprehensive compensation and rehabilitation process that would keep funds in Brazil for the Brazilian people and environment affected, including impacted Indigenous communities,” it said.

“As a non-operating joint-venture partner in Samarco, BHP Brasil does not have operational or day-to-day control of the business. BHP did not own or operate the dam or any related facilities.”

The lawsuit will test whether companies like BHP can be held accountable under international law for environmental and cultural destruction.

The outcome of the trial could have far-reaching implications for the rights of Indigenous and traditional peoples globally, especially in cases of environmental destruction caused by corporate activities.

Print

Print